The medication hydroxyurea does not seem to increase the threat of malaria infection in patients with sickle cell anemia who live in malaria-endemic regions, as per an investigation published online today in Blood, a Journal of the American Society of Hematology (ASH).

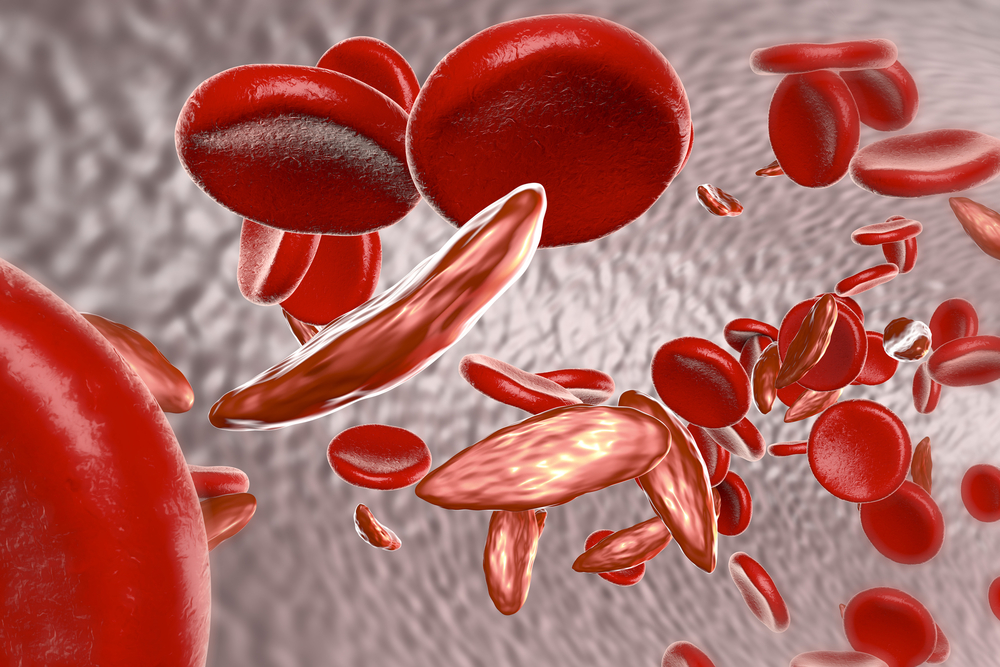

Sickle cell anemia (SCA) is an acquired issue portrayed by strange red blood cells that stick together in patients’ blood vessels, hindering the blood flow to organs, which can prompt serious torment, organ disappointment, stroke, and even death. In low-resource areas of sub-Saharan Africa, in excess of 50 percent of children with SCA die before the age of five.

Hydroxyurea, a medication suggested for kids with SCA in high-asset settings like the United States and Europe, isn’t broadly prescribed in sub-Saharan Africa, which has the most elevated weight of SCA in the world. This is somewhat a result of an absence of information that hydroxyurea will be viable and safe in low-asset areas. Specifically, some examination proposes that hydroxyurea could make individuals with SCA more susceptible to malaria, a serious and at times deadly ailment spread by mosquitoes and common crosswise over sub-Saharan Africa.

“Research has been unclear over whether the changes in immune response caused by hydroxyurea could increase the risk of malaria,” said Chandy John, MD, of Indiana University School of Medicine, principal investigator of the trial. “Because hydroxyurea provides such positive outcomes for people in high-resource regions, we want to be sure that this drug is safe for children in low-resource, malaria-prone settings.”

To comprehend if hydroxyurea use is related to higher rates of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa, specialists from the United States and Uganda set up the Novel utilization Of Hydroxyurea in an African Region with Malaria (NOHARM) preliminary, a year-long, randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled examination.

NOHARM was led on the ground by co-principal specialist Robert O. Opoka, MMED, of Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda. The group enlisted 208 kids matured 1-4 years and haphazardly assigned them into one of two treatment arms, in which they got either a fixed dose of hydroxyurea or a placebo for an entire year. All patients likewise got standard bed netting and anti-malaria medication.

“Not only were we pleased to see that the overall incidence of malaria was low, but there was also no correlation between hydroxyurea treatment and the rate or severity of malaria,” said co-principal investigator and head of data coordination Russell E. Ware, MD, Ph.D., of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

The treatment arms did not differ in terms of the incidence or severity of malaria contamination or other unfriendly events. Three kids on hydroxyurea encountered an aggregate of five malaria episodes, while seven of those receiving placebo had a total of seven malaria episodes. Two children in the hydroxyurea arm died, one from assumed sepsis and the other from obscure abrupt demise; one kid in the placebo arm passed on, probably from sepsis.

Children getting hydroxyurea likewise had lower rates of pain emergencies and hospitalizations. “Because the children prescribed hydroxyurea experienced significantly better outcomes without any increase in malaria risk, we are incredibly encouraged to further explore the drug’s use in sub-Saharan Africa,” said Dr. Ware.

As overall malaria incidence was low in the NOHARM study populace, it will be essential to monitor the rate and seriousness of malaria with hydroxyurea use in territories of higher malaria transmission. Drs. John, Ware, and Opoka are currently in the process of recruiting participants for a follow-up study to gauge the ideal dose for kids with SCD in resource-limited, malaria-prone regions.

“It is our hope that these research studies can help establish hydroxyurea as the standard of care for children with sickle cell disease in Africa,” said Dr. John.